“Hacking Grading”

Instructor feedback on writing can have an immense impact on students. Research on writing pedagogy demonstrates that students need and appreciate thoughtful feedback on their drafts in order to grow as writers. Ideally, we would be able to have one-on-one conferences with every student at every stage of writing every assignment. But due to heavy teaching loads, increasing class sizes, and limited office space/time, this is not possible for a vast majority of instructors. Therefore many – if not all – of us who teach writing intensive courses are constantly in search of grading hacks. Not only is grading student writing time consuming, it is often frustrating when the time spent seems to be ignored, misunderstood, or not internalized. These struggles are not in your head – a quick Compile search will show you hundreds of studies documenting that students have difficulty transferring the revisions suggested in written comments to future assignments. Furthermore, the traditional methods of writing in the margins using ink or electronic commenting features (for example Track Changes in Word or Suggesting mode in Google Docs) are not effective, or possible, for multimodal writing assignments including blog posts, timelines, videos, infographics, etc. After exploring a variety of approaches throughout my teaching career, I am sharing my grading hacks here as part of the 2018 MLA panel on “Hacking the Scholarly Workflow.”

The hack I describe will include pre-writing exercises and video feedback, but will focus primarily on the second phase. These tips will work for any assignment collected digitally, including Word documents, LMS posts, or media-rich compositions created in an online forum. After years of trying many platforms, I now exclusively teach using WordPress blogs. The multitude of reasons why is fodder for another post (see posts by the CUNY folks who converted me: Jim Groom, Joe Ugoretz, and Matt Gold), but can be summed up as a dedication to teaching students to learn tools that are useful and applicable outside of academia, and to have control over my own domains and data. Also, all of my assignments are to some degree multimodal, meaning they combine text-based writing with images, videos, hyperlinks, graphics, or other media. I actually wrote my dissertation and this article on the importance of teaching multimodal writing if you want to know more. One of the questions I receive most often about assigning digital compositions, is how I grade assignments that are multimodal and “turned in” on a blog. Here, I offer my response, and hope it will translate to a wide variety of writing projects.

Pre-writing exercises

Teaching students to compose in any form requires careful scaffolding. For major assignments I provide students with time to draft in class, using a variety of techniques from Pomodoro writing sprints, to design thinking brainstorming sessions, and of course lots of daily journaling. Almost all writing projects also go through peer review, organized differently for each assignment. Approaches include reverse outling, guided questions, or formal editing sessions with style sheets for upper level courses. For major – or “high-stakes” – assignments, I serve as their peer reviewer in face-to-face conferences (my institution encourages us to cancel up to 3 class sessions to be replaced with conference time with students). Therefore, when it comes time for my feedback on final drafts they should have spent a good deal of time considering previous comments and re-writing. This allows me to focus on the top three elements to prioritize in future assignments. Yes, I really try to limit myself to discussing only three areas of revision to focus on for each student.

Research

In order to provide personalized feedback on multimodal blog posts I use screen capture videos that allow me to talk through and visually highlight elements in a student’s work. The field of composition and rhetoric has explored the benefits of audio feedback across decades of scholarship:

http://comppile.org/wpa/bibliographies/Bib26/Audio_Response.pdf. You can see that some of the articles listed in the Compile Bibliography, compiled and annotated by Shannon Mrkich and Jeff Sommers, date back to 1958 when audio feedback was done via cassette recorders, so clearly this is not a new approach. In comparison to written feedback, audio feedback gives the students a chance to hear the voice of the instructor, adding clarity and a personal touch to the comments. It also eliminates the scary and often difficult to decipher “red ink” that has been scrutinized extensively in composition studies. You can see many of the more recent articles included in the Compile Bibliography explore screen capture or video feedback rather than solely audio feedback. The video element of the screen capture gives the extra dimension of the visual walk-through, so the student sees their post while hearing me describe the points where they excelled and the areas they need to work on.

Preparation

Before recording, I read the paper carefully and make notes when I encounter lovely writing, brilliant insight, and careful reflection on the assignment topic, as well as moments of ambiguity, problematic logic, and mechanical errors. These notes are then prioritized and used as a rough transcript for my video feedback to avoid rambling or disjointed commentary. Each video begins by highlighting positive attributes of the student’s work, and then leads into explaining two or three areas of improvement with examples. I end the videos with their grade, which ensures every student must watch the video all the way through (the grade is not available to them anywhere else for a couple of days). I aim to keep videos under five minutes long, ideally hovering around the three minute mark. Keep in mind, I use this for undergraduate papers from 3 to 10 pages in length. I have not attempted the same for longer, more in-depth research papers at the graduate level. I do however know that several of my colleagues and several of the articles on this process show its efficacy for basic (or remedial) writers.

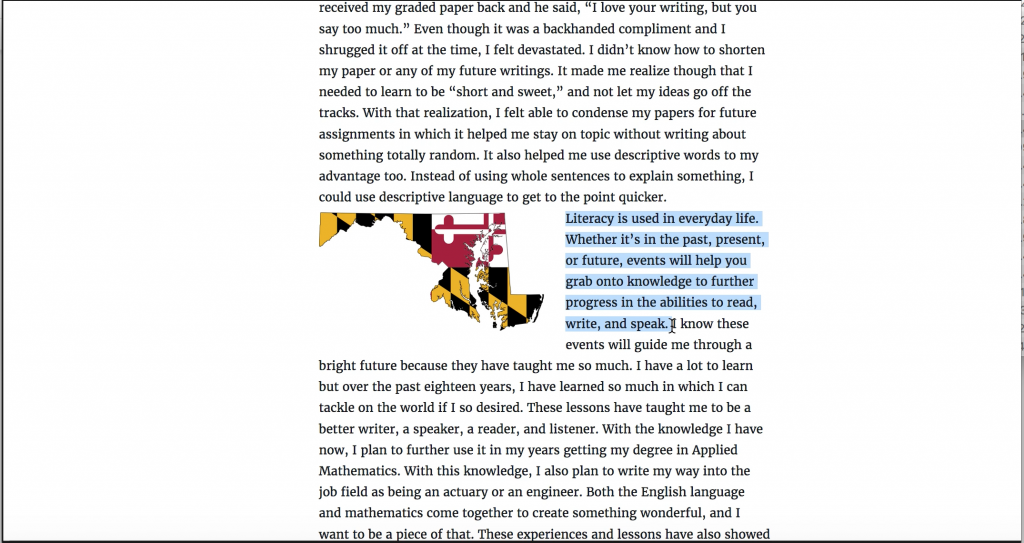

The image above shows screenshot from a sample video in which I am highlighting an area of a student’s paper while verbally explaining my advice.

The image above shows screenshot from a sample video in which I am highlighting an area of a student’s paper while verbally explaining my advice.

This method also allows me to switch tabs on the browser during the recording in order to show the student additional resources, such as OWL at Purdue exercises, language from the assignment sheet, or specific areas of the rubric that correspond to my comments.

The image above shows screenshot from a sample video in which I indicate which exercises on OWL the student would benefit from reviewing.

The image above shows screenshot from a sample video in which I indicate which exercises on OWL the student would benefit from reviewing.

Connecting my observations to online tools they can use to improve their writing in the future provides students with further explanation and alternative language in case they have trouble understanding my comments.

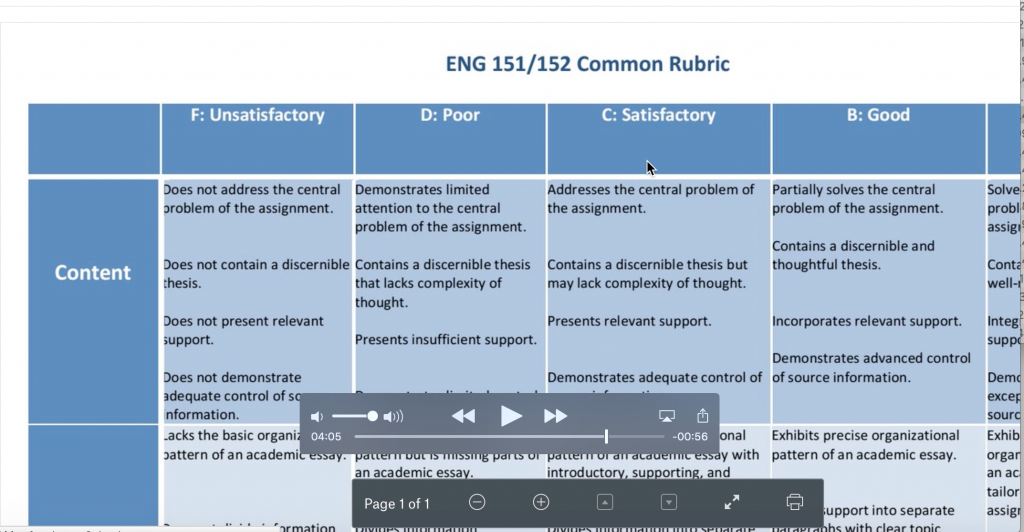

The image above shows screenshot from a sample video in which I am describe how my comments correspond to the department rubric.

The image above shows screenshot from a sample video in which I am describe how my comments correspond to the department rubric.

Referring directly to the assignment sheet and/or rubric demonstrates exactly where the assignment explains the required elements I am requesting be strengthened or improved, reminding the student to read closely and follow instructions carefully (this also eliminates the “I didn’t know we were suppose to do that…” response). As a instructor, constantly connecting my comments back to the learning objectives outlined on the rubric forces me to reflect on how clearly my assignments adhere to the goals set forth by our program.

Execution

In order to record and share these videos with students there are several options for free – or freemium – tools. As a Mac user, I rely on Quicktime to record videos. I also teach in a Mac lab, so I can use the same tool to instruct my students to make their own videos. It is important to consider which tools your student demographic will have access to when choosing your platform. For PC users, I recommend JING or SnagIt by TechSmith. There is also an Adobe option for those – like members of our film department – who teach this suite of products, and many LMS platforms include an audio feedback option (I hear Blackboard’s version is fairly user-friendly). For audio only options, most smartphones come preloaded with a free audio recorder, and Audacity is an open source tool that will do the trick.

Aside from considering which tool to use to record the videos, it is also essential to ensure that students can listen and save the videos on a variety of devices. Therefore, I save each video to a (carefully labeled) Dropbox folder using AssignmentTitle_LastName as the file name for each student. This keeps all of the videos organized on my computer, but also allows me to access them via my phone or any internet-enabled device. I use Dropbox because of the ease of link sharing across platforms. The only drawback is that you can quickly hit your storage limit if you teach multiple classes a term. This can be remedied by paying for extra storage, or by deleting old videos each year. Alternatively, you can use any cloud storage service – such as Google Drive – or save the videos to your institution’s network if there is ample storage and link sharing capabilities enabled. Just make sure that each student can only access their own video. It would violate FERPA to share an entire folder of videos with the whole class. I find it best to share individual links via email (or your LMS) with a personalized note. I typically type out a form letter, and then customize when needed. Sharing the link in an email, rather than attaching the video as a file, is much more effective for getting around size limits and spam filters. But, it is a good idea to remind students to save the video to their personal computers for future reference.

I must thank my friend Andrew Lucchesi for first introducing me to this process back in graduate school when we were both balancing a heavy class load on top of working toward graduation. Andrew convinced me of the benefits the videos offer to students with disabilities, who may struggle to read handwritten comments or digital marginalia when using screen reading technology. If you have a student who is hard of hearing, I recommend either providing captions for the video, or writing out the transcript in the email you send. I’ve also found this to be a useful technique for instructors who have disabilities and need alternative methods of grading. In fact, several of my colleagues have adopted my method after hearing rave reviews from students. It helped one of the instructors to overcome difficulties in physically dealing with large piles of papers, and it aided another in cutting down on time when teaching a 5/5 load.

Student Reactions

I have noticed that providing video feedback has improved responses on my institutional course evaluations, as these specifically ask if the course meets the learning objectives. But perhaps more significantly, students constantly refer to the video feedback in both their anonymous course evaluations comments and in their final reflection letters. It is the overwhelming gratitude and enthusiasm from the students that solidified this “hack” as a regular part of my teaching practice. As evidence, here is a small selection of unsolicited comments from the anonymous evaluations voluntarily completed by my students in Fall 2017:

“For the first paper she sent us each an individualized feedback video going over the paper, which was nice for people like me who are too shy to ask for direct help. All of her feedback was always reasonable and attainable and I feel as if I have become a better reader and writer, solely thanks to her.”

“[…] the video of comments on my essays were very helpful. Most teachers just write notes and it may be hard to understand or just isn’t explained fully. The videos actually explained what should be fixed and how it can be fixed.”

“[…] the grading videos were the most helpful and engaging because it allowed me to see the whole process and how everything comes or should come together…”

“I really appreciate the videos that show us how to improve our writing!”

As an unintended benefit, I found out that students share my videos with the writing tutors in our Academic Link tutoring center. Several of these professional tutors have emailed me thanking me for the useful feedback that helps them tailor their writing sessions with my students. Between the positive responses from students, faculty, and the writing tutors over the last five years, I can say that my experience using video feedback does match the case-studies that explicate the advantages of similar pedagogical approaches.

Although this method will take some time to get accustomed to, it is well worth the benefit to students. I’m happy to answer questions via twitter @amandalicastro or via email.